If you have been following the news in the last few weeks you will probably have seen the indictment of New York City mayor Eric Adams and the wave of resignations from his administration. A similar dynamic is playing out with GOP governor of North Carolina Mark Robinson. Both Adams and Robinson have vowed to hold on to their positions, and their examples reminded me of a quote in the Annals of Fulda about the overthrow of Charles the Fat:

Charles, struggling, renewed the war against king Arnulf, but did not accomplish [this]; with the Alemannians intimidated by fear, all defected from him, especially those he had entrusted with the business of his kingdom.1

What the annalist is hinting at here is the desertion of the elites at Charles’ court. Charles had been installed in Alemannia by his father Louis the German, and it was where he had the most entrenched support.2 After his deposition it was where Charles retreated to, presumably to build support to fight Arnulf, but his death in early 888 decisively put an end to any plans he had to regain the throne.

Yet the desertion of Charles’ men was not simply a literary device, but we can see it in Arnulf’s early charters as well. Arnulf’s first charter was a grant to Archbishop Liutbert of Mainz, who was the archchancellor for three different Carolingian rulers. Liutbert had served under Louis the German and Louis the Younger but was not as favored by Charles. By 887, however, Liutbert had regained his position and we can find him operating in this role in Charles’ charters from that year. Indeed in a last ditch effort to prevent Arnulf seizing power Charles had dispatched Liutbert with a piece of the True Cross so that Arnulf would remember the oaths he had sworn to him. Arnulf, for his part, “is regarded to have shed tears at the sight” but continued with his coup anyways. One tantalizing piece of information is a problematic charter granted, supposedly, on November 17th 887.3 Arnulf’s first charter was granted on November 27th, ten days later.

Liutbert’s support may have been critical to Arnulf. His support for Arnulf may have been a sign to other elites that the tides were turning and Arnulf was a credible ruler. The archbishopric of Mainz was one of the most important positions within East Francia, and Liutbert was a powerful figure. Arnulf’s charter thus served a very important function: it was a very public proclamation of Liutbert’s defection. The charter begins by stressing that Arnulf had been chosen by God to rule: “by a certain divine grace we were placed in front of other people.”4 Liutbert then appears as Arnulf’s “venerable and beloved archbishop.”5 If the narrative sources are right that the leaders of the kingdom were in Frankfurt for Charles’ deposition, then Liutbert’s reception of this charter would have publicly expressed his support for Arnulf’s kingship to this audience. Anyone in the audience who was on the fence about Arnulf may have been convinced by Liutbert’s support. In essence, Liutbert’s public declaration of support for Arnulf as king could have provided a “permission structure” for others to follow suit. The lack of support would have had other consequences too. That is, without courtiers such as Liutbert, the actual practice of ruling would have become harder for Charles. Kings needed elites to help diffuse royal patronage, to lead armies, and to oversee the administration of estates. Bleeding support thus had not only an ideological impact (the ruler doesn’t have a claim to rule) but also a very material one. Even routine business would have become harder if, say, Liutbert brought a bunch of scribes with him when he defected to Arnulf.6 It is worth pointing out, however, that this was not an inevitable process and Charles could have, perhaps, weathered the storm if he had survived. Louis the Pious had been abandoned twice by his men and was able to regain the throne so it isn’t unthinkable that Charles may have been able to find a way back into power.

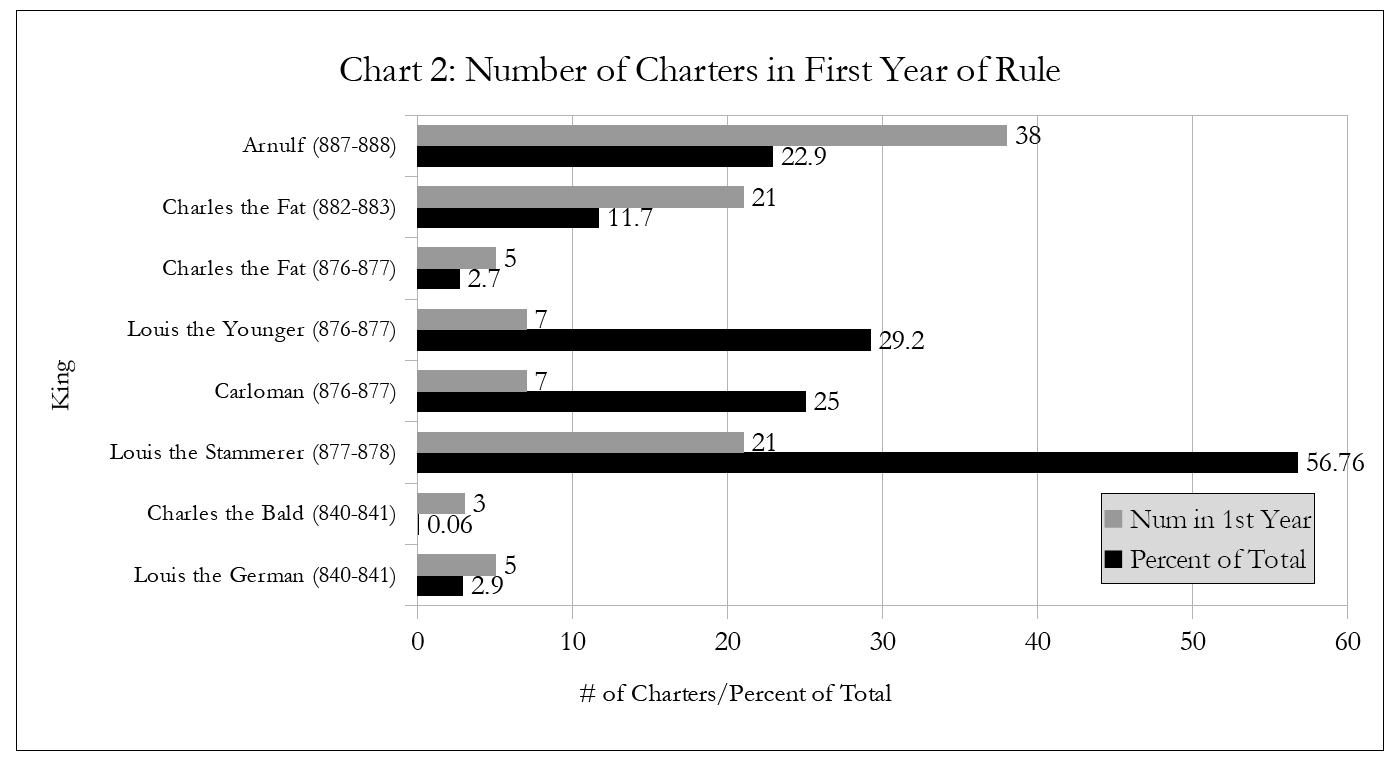

The bleeding of support may not have been as quick a process as envisioned in the narrative sources, however. Arnulf granted relatively few charters in November and December 887. The lag between November when Arnulf became king and January when charter production began to pick up is likely explained by the fact that this was a much more tense and contested period than the narrative sources let on. We have no forensic accounting of what happened between November and January, and best we can tell from Arnulf’s few charters he traveled between Frankfurt and Forcheim before ending up at Regensburg by Christmas. With Charles at large in Alemannia Arnulf needed to shore up his support in a very public way. Already at Frankfurt he had granted a charter to Liutbert, and at Forcheim he granted a charter to the abbot of Fulda Sigihard. Then at Regensburg, sometime between Christmas and early January, he received “the leading men of the Bavarians, eastern Franks, Saxons, Thuringians, Alemannians, and a large part of the Slavs.”7 The dam seems to have broken in January when Arnulf began issuing charters at a rapid pace. By the end of 888 Arnulf had issued almost forty charters, a truly gargantuan amount by Carolingian standards. Most Carolingians issued between five and seven charters in their first year of rule, so something is unusual here. Charles may have been losing supporters, but Arnulf needed to make sure that the deposed emperor couldn’t make a comeback tour.

Granting so many charters, so rapidly, was intended to secure elite support for Arnulf by giving them land and benefits, but it also would have served as multiple instances of public submission to Arnulf. The assembly in Regensburg coincides with several of these charters, suggesting they may have formed part of the ritual ceremonies of the events. As all this suggests, political transitions were often messy, and contested, processes. Even in normal circumstancces there was a jockeying for position and influence in the new court. Charles’ supporters evidently saw the tides turning and Arnulf was able to capitalize on this feeling among the elite. Ultimately that is the lesson we can draw from this: politics and political change is often driven by the feeling in the air. Whether Charles was actually too ill to rule is a different question from whether the elite believed he was. Indeed if the elite continued to believe in Charles’ abilities the coup may not have happened at all. We often like to reckon people as rational actors, strategically maximizing their own self-interests, but people rarely have perfect information. Especially in the premodern world where information could be garbled or delayed, rumors around Charles’ health may have been more exaggerated than reality, but if you were not able to see the king to tell, how would you know? When Arnulf arrived in November 887 he could capitalize on these anxieties, whether true or not. In the end Arnulf’s success may not have been because of a long term plan, although he surely harbored royal ambitions for a while, but that he could make the most of the opportunity when it appeared.

AF (B), s.a. 887, p. 115: Karolus nitens bellum contra Arnolfum regem instaurare, sed non proficit; concussis timore Alamannis, quibus maxime negotium sui regni habebat commissum, omnes penitus ab eo defecerunt.

MacLean, Kingship and Politics at the End of the Ninth Century, pp. 83-91.

D CF 172.

D A 1: quia quodammodo divina sumus gratia caeteris mortalibus praelati.

D A 1: venerando ac dilecto archepiscopo nostro.

This is something suggested by Kehr in the edition of Arnulf’s charters.

AF (B), s.a. 888, p. 116: urbe Radasbona receptis primoribus Baiowariorum, orientales Francos, Saxones, Duringos, Alamannos, magna parte Sclavanorum.